This note built upon the previous discussion of neuroimaging methods by focusing on Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) and the principles behind the MRI signal used to create structural images of the brain.

Key points:

-

Proton Precession: Thermal energy causes protons in the body to spin. In a strong magnetic field (B0), these protons align either parallel or anti-parallel to the field and precess around their own axis.

-

Relaxation: After excitation by a radio frequency (RF) pulse, protons relax back to their original alignment. This relaxation can be measured in two ways:

- Longitudinal Relaxation (T1): Time it takes for protons to recover along the z-axis (parallel to B0).

- Transverse Relaxation (T2): Time it takes for protons to lose their coherence in the xy-plane.

-

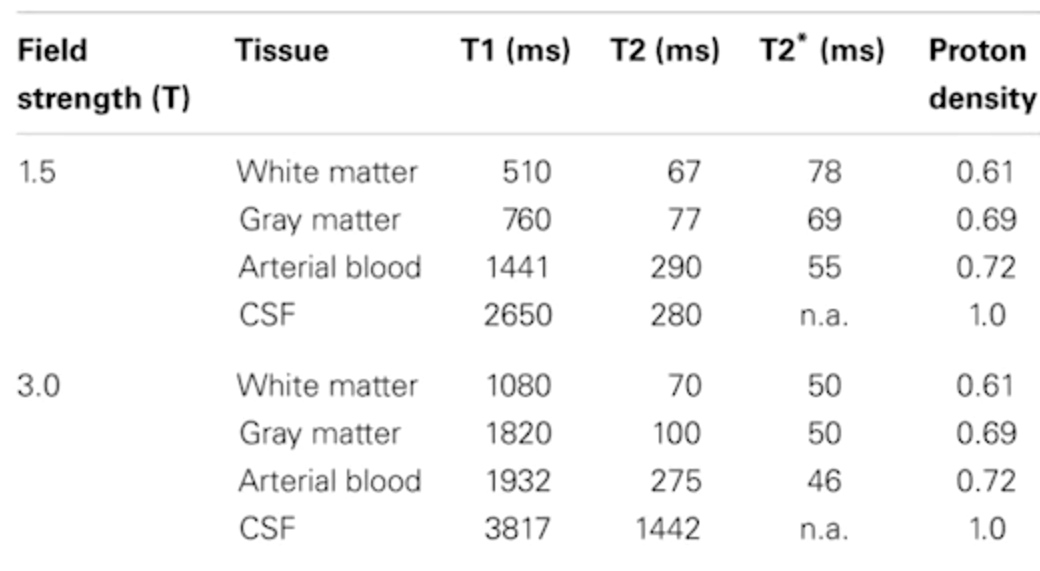

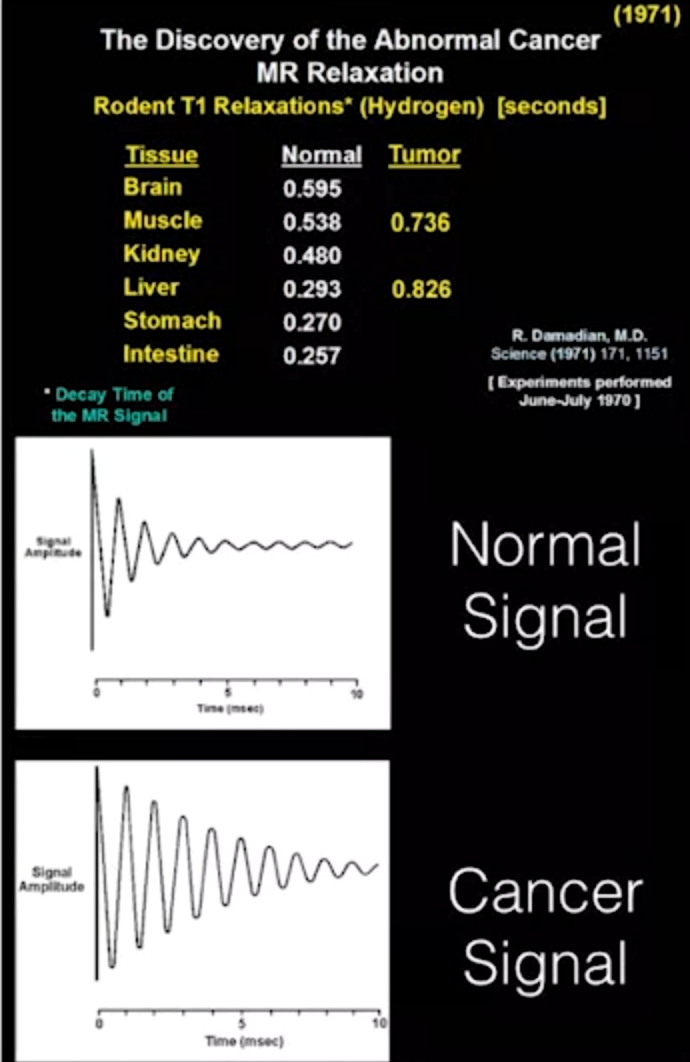

Signal Measurement: Relaxation generates a measurable signal in a receiver coil. Different tissues have different T1 and T2 relaxation times depending on their composition (fat, water content).

-

Relaxation time of different biological matter

-

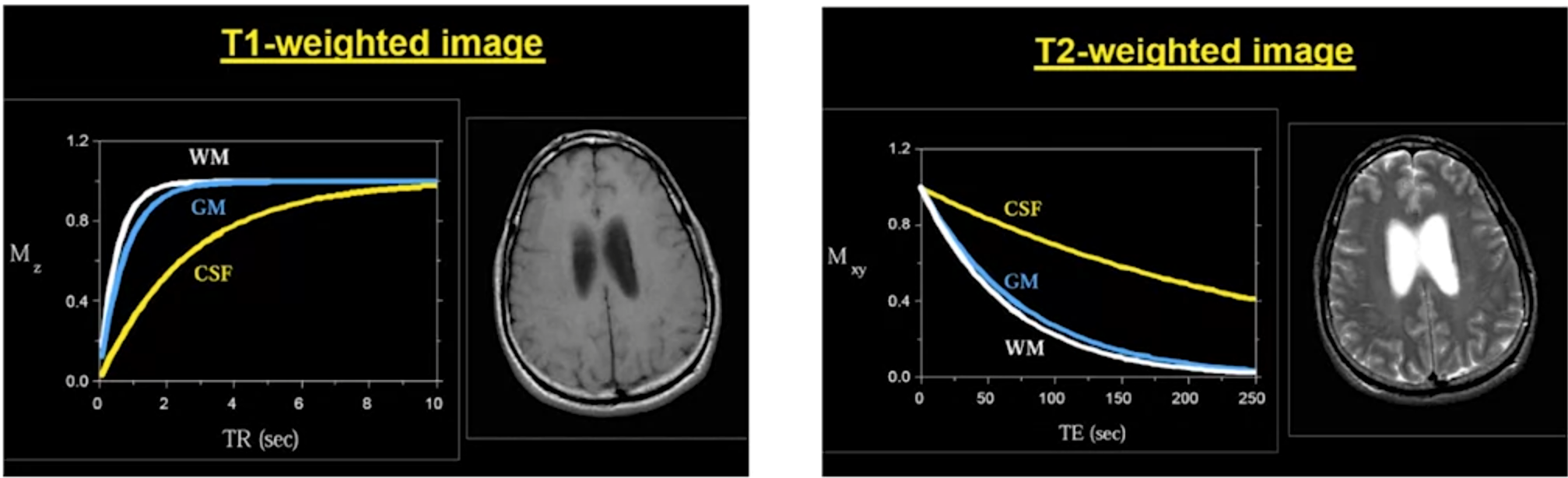

Image Contrast: By measuring T1 and T2 relaxation times, we can distinguish between different tissue types. This forms the basis for structural MRI images.

- T1-weighted Images: CSF appears dark, gray matter intermediate, and white matter bright.

- T2-weighted Images: CSF appears bright, and gray and white matter appear as different shades of gray.

-

Spatial Specificity: To determine the location of the signal within the volume, MRI uses:

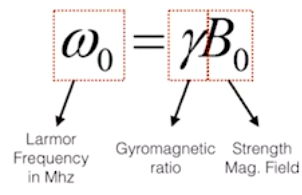

- Larmor Frequency: The specific frequency needed to excite protons depends on the magnetic field strength and the type of tissue.

- Gradient Fields: Small magnetic fields that vary linearly in one direction. By changing the gradient, we can select a specific slice for excitation.

- Larmor Frequency: The specific frequency needed to excite protons depends on the magnetic field strength and the type of tissue.

-

Pulse Sequences: Combinations of RF pulses and gradients used to define different imaging sequences. Varying these sequences allows us to highlight different tissue properties (T1-weighted, T2-weighted, etc.).

Resourses