fMRI Task Design Lecture Notes: In-Depth Summary

This note delved into designing effective tasks for fMRI experiments. The central goal is to leverage stimuli to induce a specific psychological state within the participant and subsequently measure the corresponding brain activity.

Technical Constraints:

- Confined Scanner Environment: Participants are positioned within a scanner bore, limiting their movement. This necessitates careful consideration for stimulus presentation and response collection.

- Stimulus Presentation and Response: Visual stimuli must be large and bright for clear visibility through a mirrored viewing system inside the scanner. Button response options are also limited due to hand placement within the scanner (typically two to four buttons per hand).

- Temporal Considerations: Event-related designs require variable timing between stimuli presentations to ensure proper analysis of the blood-oxygen-level-dependent (BOLD) response. Additionally, scan runs should be limited to 4-6 minutes each to minimize scanner drift caused by thermal buildup. The overall experiment should ideally be completed within 60 minutes to balance data collection needs with participant comfort.

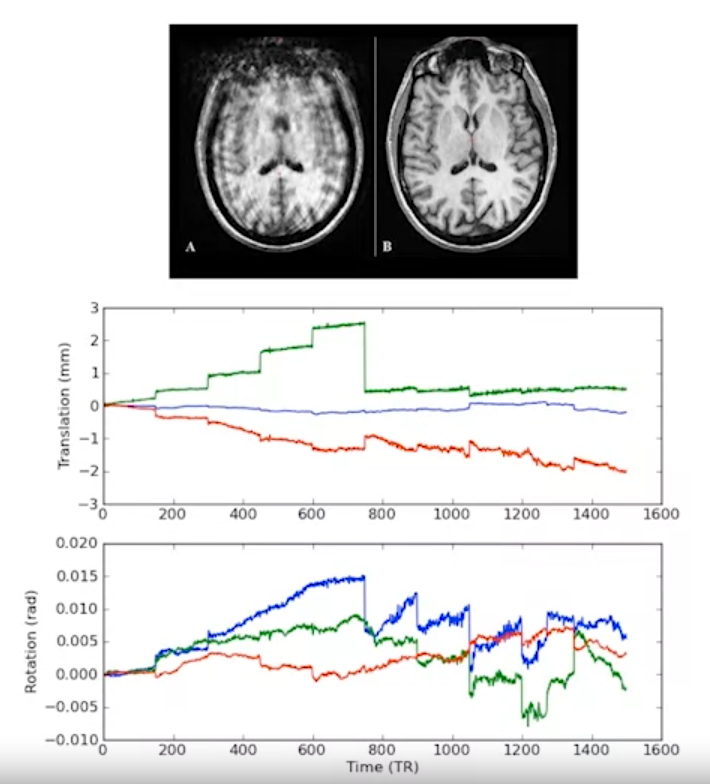

- Motion Control: Even small head movements can significantly impact fMRI measurements. Padding is used to restrict motion, but this can decrease participant comfort during the experiment.

Psychological State Considerations:

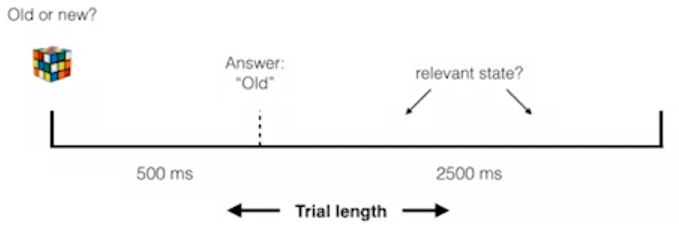

- Task Engagement and Duration: The designed task must effectively induce and sustain the target psychological state throughout the entire trial duration. If the task is too short, the brain may not have sufficient time to reach the desired state, while an excessively long trial might lead participants to lose focus and engage in unrelated thoughts.

- Strategic Task Solving: It’s important to avoid designs where participants can employ shortcuts to solve the task, as this can reduce the validity of the measured cognitive state.

- Task Complexity and Trial Length: The time required to complete the task should be carefully considered in relation to the trial length. Overly complex tasks may necessitate longer trials to ensure participants have sufficient time to process the information and respond.

- Eliciting Emotional Responses: Emotional responses are inherently slow to change. Designing tasks that induce emotional states requires factoring in additional time to allow participants to transition between different emotional states during the experiment.

Statistical Design Considerations:

- Independent and Dependent Variables: A critical step involves identifying the independent variables (factors being manipulated) and the dependent variables (brain activity being measured) within the experiment. Understanding how these variables will be manipulated is essential for proper design.

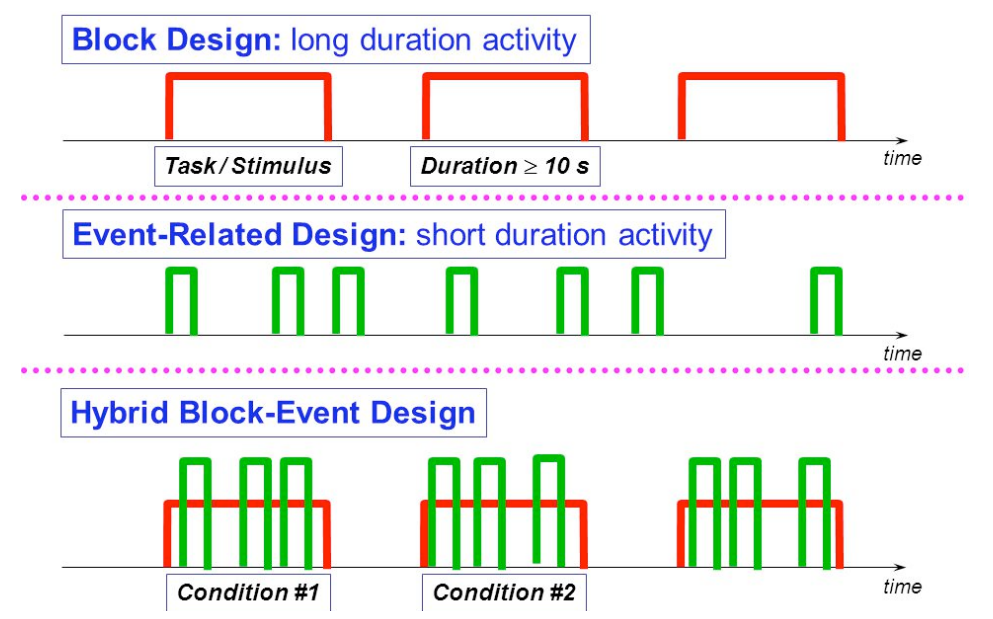

- Stimulus Organization: The experiment design dictates how the stimuli will be presented. Block design involves presenting a series of stimuli within a block followed by a rest condition. Event-related design focuses on analyzing the brain activity elicited by individual stimuli. Hybrid designs combine elements of both block and event-related designs, offering more flexibility in data analysis.

Common Experimental Designs in fMRI:

Subtraction Design:

- This is one of the simplest and most commonly used designs

- It involves comparing brain activation between two conditions:

- An experimental or “active” condition designed to elicit the cognitive process of interest

- A control or “baseline” condition designed to account for basic sensory/motor processes

- By subtracting the activation during the control condition from the active condition, the remaining areas are presumed to reflect neural processing specific to the cognitive process being studied

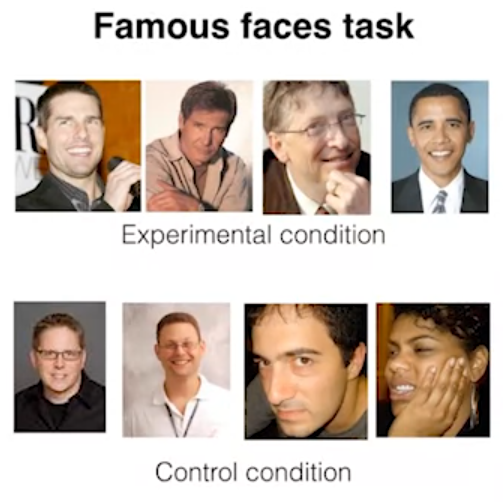

- Example: Famous faces task

- Active: View famous/familiar faces

- Control: View unfamiliar faces

- Subtraction isolates brain regions involved in face recognition/familiarity

- Advantages: Simple and interpretable when cognitive processes are categorical/discrete

- Limitations: Cannot dissociate sub-components, oversimplifies many cognitive processes

Factorial Design:

- Allows studying the main effects of multiple factors and their interactions in one experiment

- Has at least two independent variables, each with multiple levels

- Full factorial design crosses all combination of factor levels

- Example: Studying spatial navigation with factors of boundary shape and enclosure

- Curvilinear open, curvilinear enclosed, rectangular open, rectangular enclosed

- Can test main effects of shape and enclosure, plus their interaction

- Advantages: Increased experimental efficiency, can isolate interactions

- Limitations: Interactions can be difficult to interpret, many conditions reduces power

Parametric Design:

- Used when the cognitive process of interest varies parametrically with task difficulty/demand

- Systematically varies one parameter across multiple levels of the task

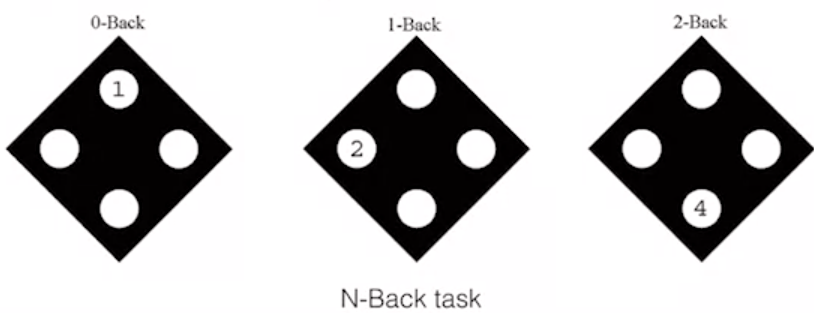

- Example: N-back working memory task

- 0-back: Identify currently shown digit

- 1-back: Identify digit shown one trial before

- 2-back: Identify digit from two trials before

- Higher N-back levels increase working memory load parametrically

- Looks for brain areas where activation changes linearly/monotonically with difficulty level

- Advantages: Highly efficient design, models graded nature of cognitive processes

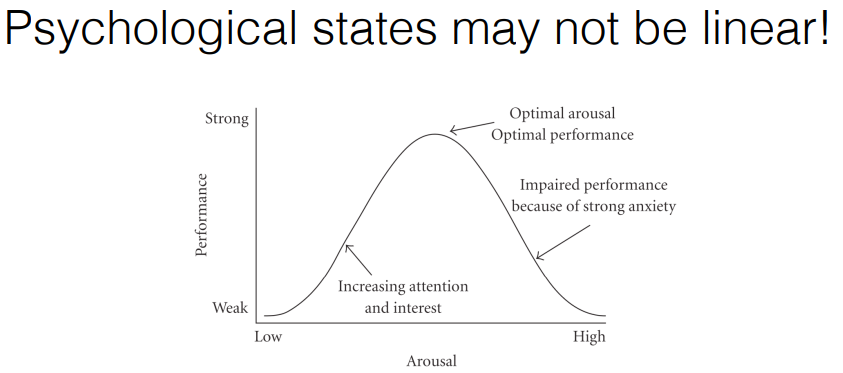

- Limitations: Assumes linear relationship, tasks may asymptote or show non-monotonic patterns

-

-

-

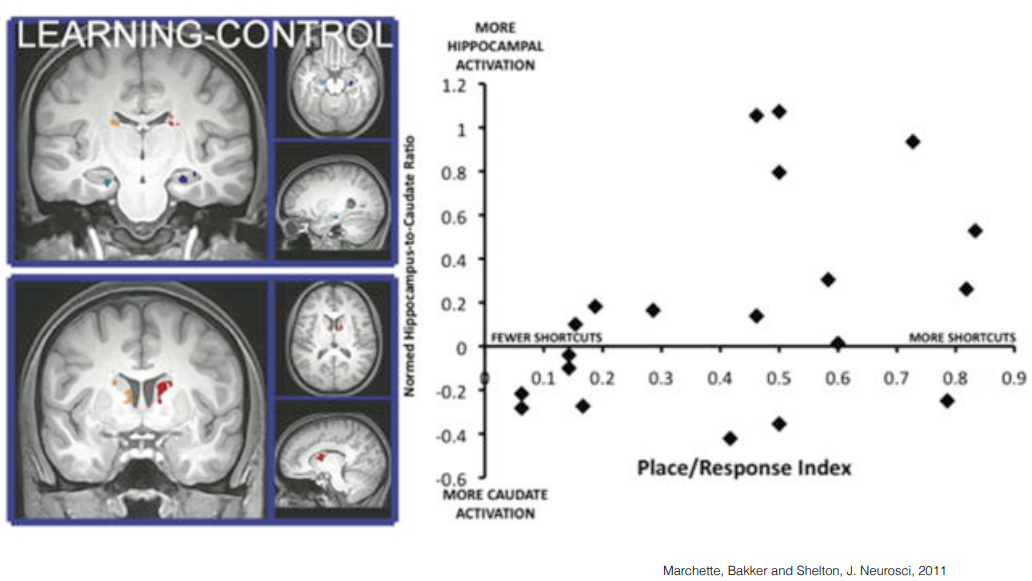

Individual Differences Design:

- Correlates measured brain activation with behavioral performance across subjects

- No strict experimental and control conditions

- Task designed to allow variability in performance measures of interest

- Example: Spatial navigation brain activations correlated with memory test scores

- Advantages: Direct brain-behavior mapping, can identify compensatory mechanisms

- Limitations: Correlational results cannot determine causality, difficult interpretability

Outcome Measures Design:

Outcome Measures Design: - Tests effects of interventions/manipulations on brain function and cognition

- Within-subject design - each participant scanned before and after intervention

- Example interventions: Drug, training/practice, brain stimulation, exercise, etc.

- Pre vs post activation compared to reveal neural changes from intervention

- Advantages: Powerful way to assess causal effects on brain

- Limitations: Practice effects, difficult to match baseline task versions

The fundamental tradeoff in Experimental Design

- Fewer condition results in better power but less specificity

- More conditions result in worse power but better potential for inference

Stimulus Design Options:

How will the stimuli be organized

- Block Design: A series of stimuli are presented within a block, followed by a rest condition for comparison.

- Event-Related Design: This design focuses on the response to individual stimuli, allowing researchers to examine the temporal dynamics of brain activity.

- Hybrid Design: This design combines elements of both block and event-related designs, providing more flexibility in data analysis depending on the specific research question.

Careful experimental design and selection of experimental and control conditions is critical to the outcome of the study